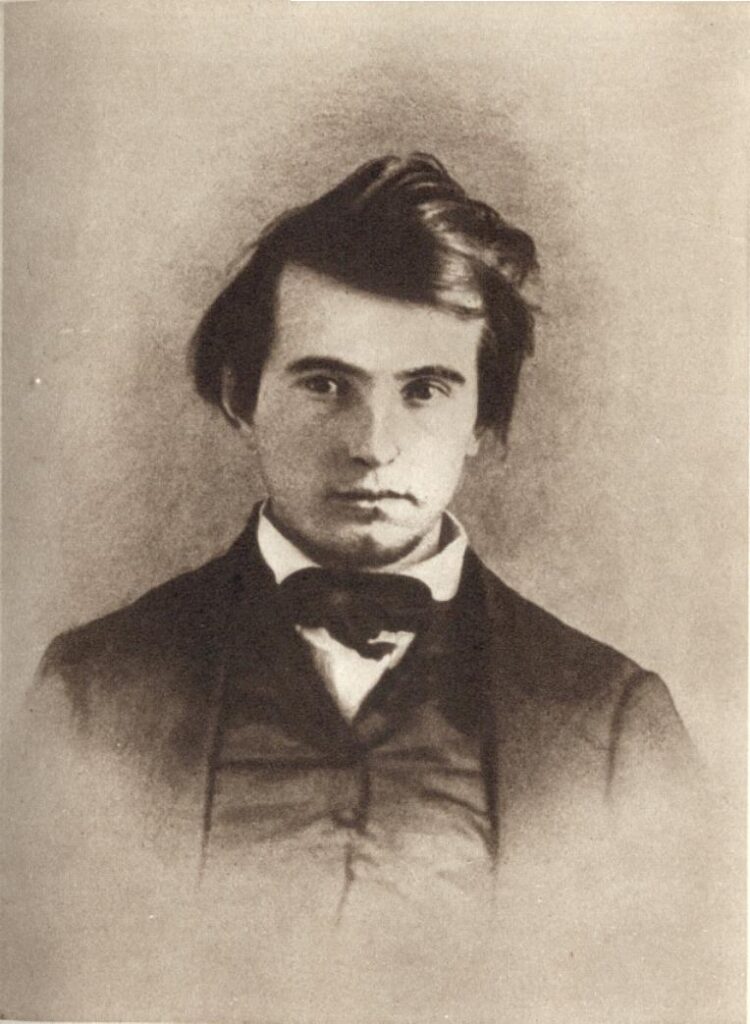

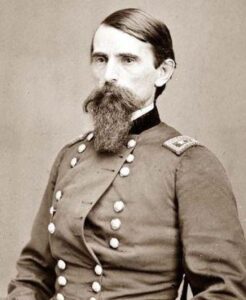

In January of 1851, 24-year old Lewis Wallace was raised a Master Mason at Fountain Lodge 60 in Covington, Indiana, just three years after the lodge had been chartered by the Grand Lodge. Lawyer, statesman, army general, diplomat, inventor and Renaissance man, Lew Wallace would become the best-selling author of the 19th century.

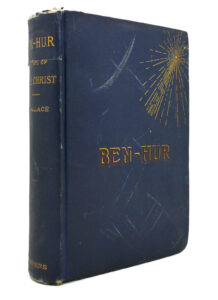

Lew Wallace may not be a well-known name today, but less than 30 years after becoming a Mason, he would be internationally known as the author of the world’s most popular novel, Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ. First published in 1880, the epic story of love, betrayal, cruelty, vengeance, faith and redemption, wrapped in a sweeping adventure out of the age of Romance, captured the imaginations of millions. The book inspired countless readers to convert to Christianity, or gave new purpose to lapsed Christians who rediscovered their own faith. Ben-Hur remained the most successful novel of all time up until Gone With the Wind’s publication in 1936. It has never gone out of print.

Brother Lew Wallace’s handwritten petition for the degrees of Freemasonry is still a prized possession of Fountain Lodge 60 today. Several years after the end of the Civil War, he moved and made his home in Crawfordsville, where he transferred his membership to Montgomery Lodge 50 before his death in 1905.

Now, thanks to a generous agreement with the Lew Wallace Study and Museum in Crawfordsville, the Masonic Library & Museum of Indiana is proud to display the Masonic apron worn by both author and statesman Lew Wallace, and his father, Indiana Governor David Wallace when they each first joined the fraternity.

*. * *

Born April 10th of 1827, Lew (he preferred the informal version of his name) had grown up in the shadow of his father, who had served as the sixth governor of the state of Indiana between 1831 and 1837, and as an Indiana Congressional Representative between 1941 and 1843 (David Wallace was himself a member of Harmony Lodge 11 in Brookville and joined in 1826). Lew was an incorrigible child who took full advantage of his father the governor’s important positions. He was a notorious discipline problem and in constant search of excitement and adventure, which often landed him in trouble with neighbors. At the age of six he was already threatening to run away from home and stow away on a steamboat.

Born April 10th of 1827, Lew (he preferred the informal version of his name) had grown up in the shadow of his father, who had served as the sixth governor of the state of Indiana between 1831 and 1837, and as an Indiana Congressional Representative between 1941 and 1843 (David Wallace was himself a member of Harmony Lodge 11 in Brookville and joined in 1826). Lew was an incorrigible child who took full advantage of his father the governor’s important positions. He was a notorious discipline problem and in constant search of excitement and adventure, which often landed him in trouble with neighbors. At the age of six he was already threatening to run away from home and stow away on a steamboat.

Lew’s father refused to pay for college, so he went to work at age 16 in the Marion County clerk’s office. He began to study law at his father’s law firm in Indianapolis, but in 1846 at the age of 19, he became a recruiter seeking volunteers for the Mexican-American War (1846-48). When the U.S. Civil War began in 1861, he was made the commanding officer of a brigade of Indiana militia volunteers, and was acclaimed for his role in the daring capture of the Confederate Fort Donelson, which overlooked the Cumberland River on the Kentucky/Tennessee border. In 1862 at the age of 34, he was made the youngest major general in the entire Union army.

Lew’s military career and reputation were wrecked by the Battle of Shiloh, after a miscommunication over confused orders issued by General Ulysses S. Grant contributed to an enormous number of Union casualties. Wallace had acted properly and successfully led his troops during the battle, but he became Grant’s scapegoat for many years during and after the end of the war for the terrible losses. Lew was stripped of active command, and what had looked like a brilliant future military career was brought to a sudden and ignominious stop. He was furious at Grant’s betrayal and spent years trying to restore his good name and character. Nevertheless, he continued to serve with distinction wherever he could throughout the conflict, later leading local volunteer troops to repel Confederate attacks on Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. It wasn’t until Grant wrote his autobiography in the 1870s that he admitted his own errors at Shiloh in print and finally vindicated Lew Wallace.

Lew’s military career and reputation were wrecked by the Battle of Shiloh, after a miscommunication over confused orders issued by General Ulysses S. Grant contributed to an enormous number of Union casualties. Wallace had acted properly and successfully led his troops during the battle, but he became Grant’s scapegoat for many years during and after the end of the war for the terrible losses. Lew was stripped of active command, and what had looked like a brilliant future military career was brought to a sudden and ignominious stop. He was furious at Grant’s betrayal and spent years trying to restore his good name and character. Nevertheless, he continued to serve with distinction wherever he could throughout the conflict, later leading local volunteer troops to repel Confederate attacks on Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. It wasn’t until Grant wrote his autobiography in the 1870s that he admitted his own errors at Shiloh in print and finally vindicated Lew Wallace.

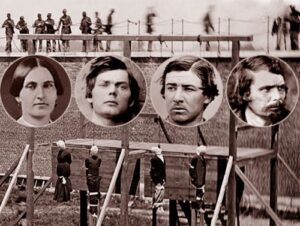

Following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth in April 1865, Wallace was appointed to the commission that investigated and convicted eight co-conspirators in the murder plot. He was also appointed as the head of a committee that court martialed Henry Wirz, the former commandant of the South’s notorious Andersonville prison camp. Out of 45,000 Union troops held prisoner in the woefully over-crowded camp, more than a third of them had died from dysentery, scurvy and starvation. Wallace was in a unique position to investigate the actions of Wirz because he had briefly served in 1862 as the commander of one of the North’s own prison camps, Camp Chase, in Columbus, Ohio. Wirz was found guilty of war crimes by the commission and executed.

Wallace had long wanted to write novels. In the 1840s, he had written a manuscript called The Fair God, but it wasn’t published until 1873, and it was only marginally successful. But it was enough to convince Lew he had a future as a novelist. After the war ended, Wallace returned to his home in Crawfordsville and began to work on what was first intended to be a short novel about the Magi, the three “wise men” who follow the Star of Bethlehem to Nazareth and pay homage to the newborn baby Jesus. On a train trip in 1876, Wallace had encountered a man named Robert Ingersoll, who was nationally known as “The Great Agnostic.” Ingersoll was an extremely opinionated and powerful orator who advocated what was then known as “Free Thought” in all matters—what would probably be called a “Progressive” these days. Ingersoll advanced the writings of Thomas Paine from the previous century and the belief that the Bible had been written, not by the word of God, but by the well-intentioned hands of men who had simply made up miracles, virgin births, and resurrections.

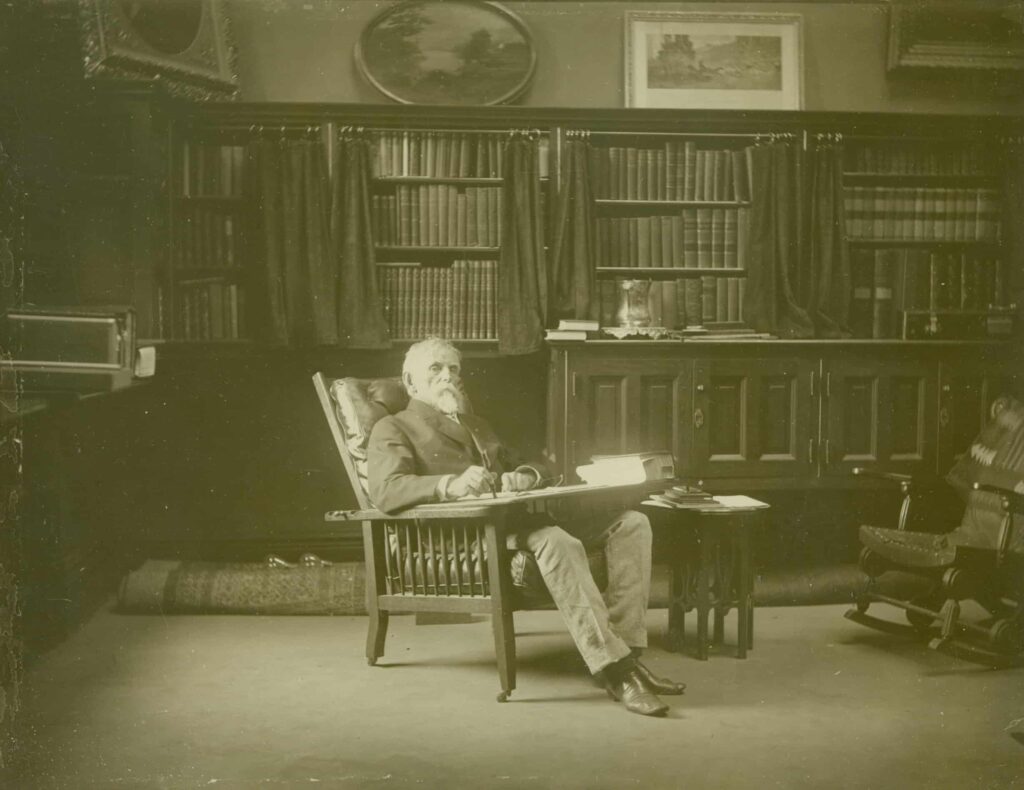

The two men talked into the night as the rain rolled on. Like all Masons, Lew Wallace had affirmed a belief in God upon joining Fountain Lodge back in his twenties, but he had never seriously given much thought to his faith before. He had never been a regular churchgoer or involved in any formally organized religion, but he later wrote that he had a “Christian conception of God” from his family’s Methodist traditions. The conversation with Ingersoll suddenly motivated him to explore what he truly believed and why. The day after his return home, he pulled a chair up under a beech tree in his back yard outside of his personally designed private study and man cave, grabbed a small hand-held chalkboard, and began to plot out an outline for a story.

Wallace was a voracious reader, and a visit to his private study today reveals a huge collection of the major books of faith from all over the world. He also made a detailed study of the geo-political history of the Middle East during the Roman occupation, along with the architecture, clothing and customs of the period, all from the comfort of his own library. That kind of care can be found throughout the novel. In 1878, Wallace was appointed territorial governor of New Mexico by president Rutherford B. Hayes. He finished the Ben-Hur manuscript while living there, and submitted it for publication. It was released in 1880 to almost instant acclaim.

Wallace was a voracious reader, and a visit to his private study today reveals a huge collection of the major books of faith from all over the world. He also made a detailed study of the geo-political history of the Middle East during the Roman occupation, along with the architecture, clothing and customs of the period, all from the comfort of his own library. That kind of care can be found throughout the novel. In 1878, Wallace was appointed territorial governor of New Mexico by president Rutherford B. Hayes. He finished the Ben-Hur manuscript while living there, and submitted it for publication. It was released in 1880 to almost instant acclaim.

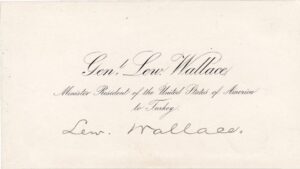

Incoming president James A. Garfield was such a fan of Ben-Hur when it appeared that he appointed Wallace to be ambassador to the Ottoman Empire in Constantinople in the hope that actually living for a while in the region of the Holy Land would motivate him to write a sequel. Wallace’s role as U.S. Minister to the Ottoman sultan required him to deal sensitively with important and impassioned people of many often-conflicting faiths. He did an excellent job, while becoming close friends with Sultan Abdul Hamid. Few have connected and credited his Masonic background and his own personal struggles for his success. He and the sultan had long conversations about their beliefs, and the two men had enormous respect for each other’s diplomacy. In fact, when Wallace was replaced under the next American administration, the sultan repeatedly requested for him to be reappointed, and even sent a personal messenger to Crawfordsville to convince him to come back.

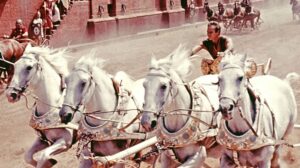

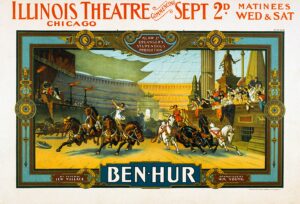

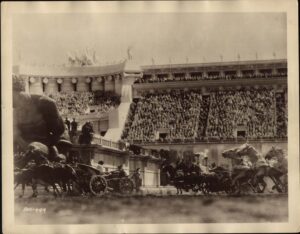

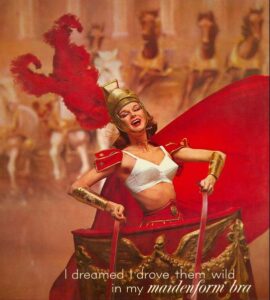

Lew’s son Henry was a shrewd businessman and promoter, and the book’s success led to the first examples of product tie-ins. Henry licensed the name of the book and the performance rights of the story itself to all kinds of companies and organizations. The novel Ben Hur spawned technically complex theatrical adaptations that featured live horses and chariots onstage for the racing sequence, multiple movie versions, radio dramas and tie-in products, from Ben-Hur soap, perfume and flour, to namesake cars, bicycles, cigars and more. A fraternal “secret society” called the Supreme Tribe of Ben-Hur was established in 1894 for both men and women, and offered life insurance benefits to its members. (The fraternal group died in the 1970s, but their insurance business eventually became USA Life Insurance.)

Lew’s son Henry was a shrewd businessman and promoter, and the book’s success led to the first examples of product tie-ins. Henry licensed the name of the book and the performance rights of the story itself to all kinds of companies and organizations. The novel Ben Hur spawned technically complex theatrical adaptations that featured live horses and chariots onstage for the racing sequence, multiple movie versions, radio dramas and tie-in products, from Ben-Hur soap, perfume and flour, to namesake cars, bicycles, cigars and more. A fraternal “secret society” called the Supreme Tribe of Ben-Hur was established in 1894 for both men and women, and offered life insurance benefits to its members. (The fraternal group died in the 1970s, but their insurance business eventually became USA Life Insurance.)

In 1925, an authorized silent production of Ben-Hur featuring Roman Navarro as Judah and Francis X. Bushman as Messala was the very first movie made by the newly established Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio.

Presaging the Star Wars era, the epic 1959 MGM remake directed by William Wyler with Charleton Heston as Judah and Stephen Boyd as Messala won a record number of Academy Awards (11 in all, out of 12 nominations) and resulted in a line of Ben-Hur action figures and countless commercial tie-ins as it had in the 1920s.

Because of Lew Wallace’s example and reputation, Crawfordsville took on the banner of “the Athens of Indiana.”

His unique, freestanding writing study, located on the grounds of his now mostly-razed Crawfordsville home where he had written much of the book, is a fascinating museum today, and became a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

His unique, freestanding writing study, located on the grounds of his now mostly-razed Crawfordsville home where he had written much of the book, is a fascinating museum today, and became a National Historic Landmark in 1976.

Lew Wallace’s statue in the U.S. Capitol Building’s famed Statuary Hall, one of Indiana’s two official statues that each state may display (the other being of Governor and Freemason Oliver P. Morton), has stood there since 1910. Out of the 100 figures in the Capitol currently exhibited, Wallace’s remains the only sculpture of a novelist from any state, though he’s one of at least thirty who were Freemasons.

Lew Wallace’s statue in the U.S. Capitol Building’s famed Statuary Hall, one of Indiana’s two official statues that each state may display (the other being of Governor and Freemason Oliver P. Morton), has stood there since 1910. Out of the 100 figures in the Capitol currently exhibited, Wallace’s remains the only sculpture of a novelist from any state, though he’s one of at least thirty who were Freemasons.

In 1895, Wallace transferred his membership to Montgomery Lodge in Crawfordsville, as it was just down the street from his home. He had been a part of the laying of the cornerstone for the Montgomery Lodge building, and played a prominent role in the dedication ceremony marking its completion in 1904.

In what was to be his final speech, Wallace talked of several things, but became visibly moved and wept as he spoke with pride and reverence with respect to the Masonic apron he was wearing, as it had belonged to his beloved father 50 years earlier. Not long after this event, Wallace’s health quickly declined, and just a few months later, he passed away in February of 1905.

In what was to be his final speech, Wallace talked of several things, but became visibly moved and wept as he spoke with pride and reverence with respect to the Masonic apron he was wearing, as it had belonged to his beloved father 50 years earlier. Not long after this event, Wallace’s health quickly declined, and just a few months later, he passed away in February of 1905.

Ben-Hur may not make it onto many modern-day reading lists (more’s the pity), but its story remains just as compelling today as it was more than a century ago. The silent 1925 film is frequently run on Turner Classic Movies’ ‘Silent Sundays’ program, and the classic 1959 Charleton Heston version is usually run during the Christmas and Easter seasons. In 2010, there was a TV miniseries made of the story with Joseph Morgan and Stephen Campbell Moore. And in 2016, a new theatrical film was released starring Jack Huston and Toby Kebbell.

The story of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ

Lew Wallace’s Freemasonry is arguably reflected throughout Ben Hur and in its characters. Much of it is set in Roman-occupied Judea, in the shadow of Jerusalem’s Mount Moriah and the Second Temple, and if ever a literary story touched a wide, cross-section of different faiths, it was Ben-Hur. Nearly every major and minor character in the story has a different religious belief, but they all have their own personal perception of the “One True God.”

* * *

Judah Ben-Hur is a young Hebrew prince of Judea, living in a palace in Jerusalem, when his childhood friend Messala returns from years in Rome. As boys who were raised side by side in Jerusalem, they had been as inseparable as brothers. But as an adult, Messala has become an arrogant and ruthlessly ambitious military man, while Judah now recoils at Rome’s heavy-handed occupation of the land and mistreatment of his people. When he refuses to help Messala root out anti-Roman revolutionaries, the two former friends become bitter enemies.

While watching a parade of fresh Roman troops entering the city from the palace rooftop, Judah Ben-Hur’s sister knocks loose a roofing tile, which falls and slightly wounds a Roman officer. Soldiers immediately burst into the complex and arrest Judah and the two women. In retaliation for their “crime” of attacking Romans, his mother and sister are immediately imprisoned, and Judah is carried off in chains to serve as a slave in the Roman galleys. Messala does nothing to intervene on behalf of his old friend or the family who had treated him as their own son, and Judah vows to return one day and have vengeance on him.

While being marched to the Mediterranean coast through the scorching Judean desert, Judah is cruelly prevented by Roman guards from drinking any water when the rest of the prisoners stop briefly at a well. Suddenly, a stranger appears and silently walks to the well. He draws water and gives a cup to Judah, while the guards are strangely awestruck by the stranger’s intense gaze and compassion. The stranger is Jesus, and Judah is haunted by the memory of his kindness and his radiant face that day.

Judah spends five years below the decks of Roman ships, pulling on the oars while seething with hatred, and dreaming of revenge. During a fierce battle at sea, Judah’s ship is destroyed and sinks, but he manages to survive by clinging to the wreckage. By a bizarre twist of fate, he saves the life of the Roman commander of the fleet, who takes him to Rome and gratefully adopts Judah as his own son. The emperor Tiberius declares the former Hebrew prince to now be a Roman citizen, and he is hailed as a hero. But Judah longs to return to Judea in order to discover the fate of his mother and sister, and have his revenge on Messala. He must wait another two years, and during this time, he becomes renowned as one of the finest charioteers in the Empire.

At last, Judah is finally able to return to his homeland. Upon landing in Judea, he encounters Balthazar, one of the three wise Zoroastrian magi who had followed the star over Bethlehem to the site of Christ’s birth, and has become a Christian while following Jesus’ ministry. He is also befriended by Prince Ilderim, an Arab sheik who convinces Judah to drive the sheik’s dazzling team of four Arabian horses in a chariot race at Antioch against Messala. After a brutal race – the highlight of the story – Messala dies of his injuries. As a final act of hatred, he tells Judah that his mother and sister have not died in prison, but have become lepers. Judah rescues the women from the Valley of the Lepers, and, recalling Balthazar’s telling of Christ’s miracles, he tries to take them to Jesus to cure them, only to discover that he’s been sentenced to crucifixion.

Judah and the two women arrive at Golgotha just as Christ utters his last cries to God and dies on the cross. In the terrifying thunderstorm that follows, the rain cleanses the women of leprosy. Judah realizes that Jesus is the Messiah, sent to cleanse the world of its sins through his suffering and death. Judah is redeemed, and renounces his life of violence and revenge in order to follow Jesus’ teachings of peace.