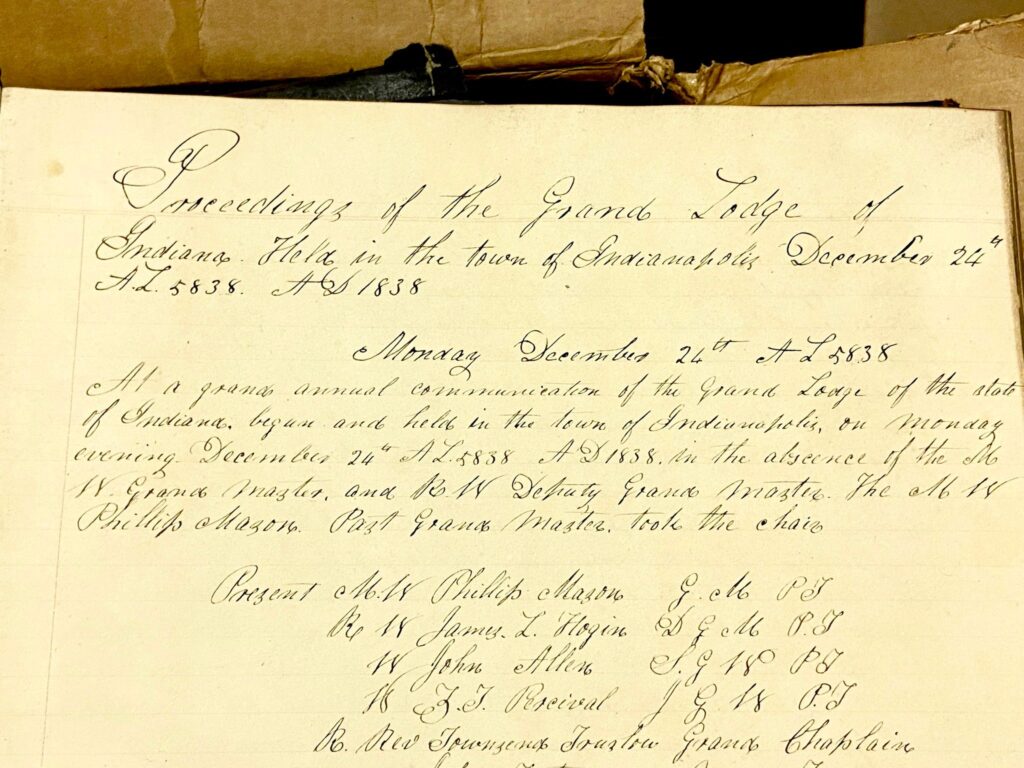

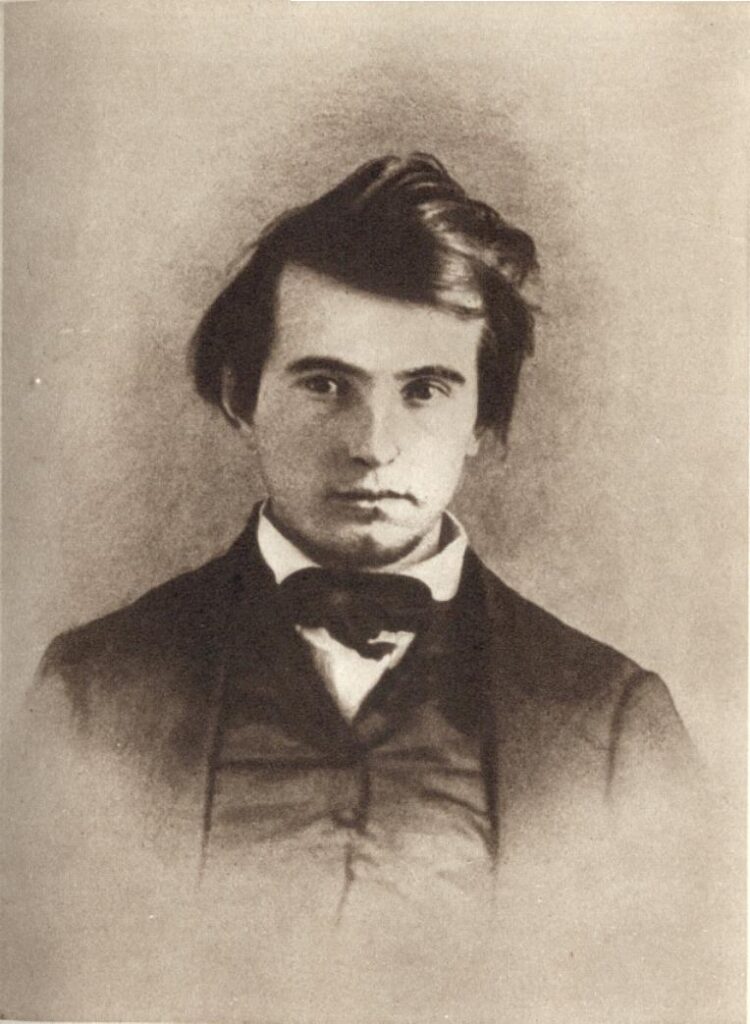

In January of 1851, 24-year old Lewis Wallace was raised a Master Mason at Fountain Lodge 60 in Covington, Indiana, just three years after the lodge had been chartered by the Grand Lodge. Lawyer, statesman, army general, diplomat, inventor and Renaissance man, Lew Wallace would become the best-selling author of the 19th century.

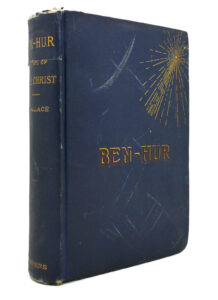

Lew Wallace may not be a well-known name today, but less than 30 years after becoming a Mason, he would be internationally known as the author of the world’s most popular novel, Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ. First published in 1880, the epic story of love, betrayal, cruelty, vengeance, faith and redemption, wrapped in a sweeping adventure out of the age of Romance, captured the imaginations of millions. The book inspired countless readers to convert to Christianity, or gave new purpose to lapsed Christians who rediscovered their own faith. Ben-Hur remained the most successful novel of all time up until Gone With the Wind’s publication in 1936. It has never gone out of print.

Brother Lew Wallace’s handwritten petition for the degrees of Freemasonry is still a prized possession of Fountain Lodge 60 today. Several years after the end of the Civil War, he moved and made his home in Crawfordsville, where he transferred his membership to Montgomery Lodge 50 before his death in 1905.

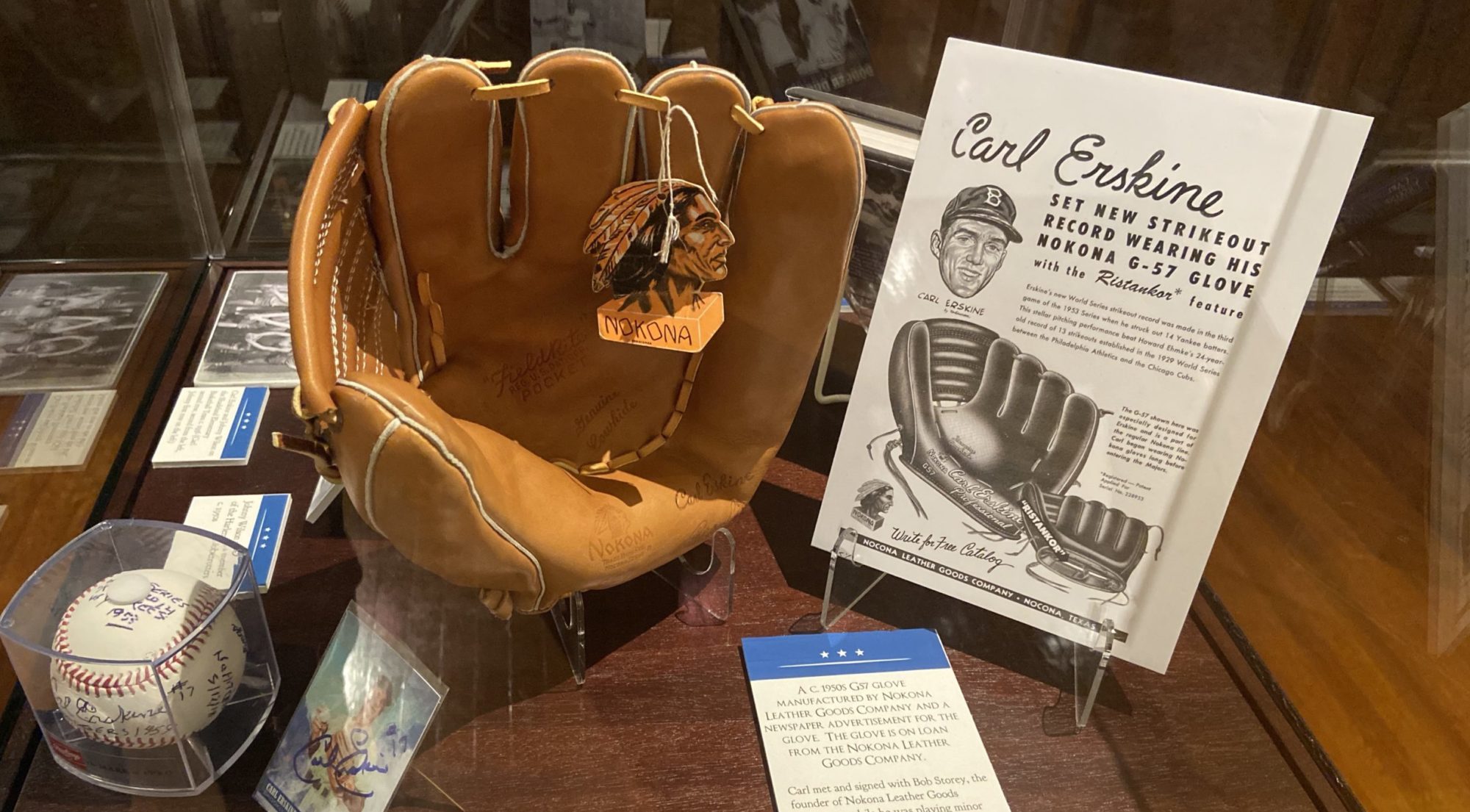

Now, thanks to a generous agreement with the Lew Wallace Study and Museum in Crawfordsville, the Masonic Library & Museum of Indiana is proud to display the Masonic apron worn by both author and statesman Lew Wallace, and his father, Indiana Governor David Wallace when they each first joined the fraternity.

*. * *

Born April 10th of 1827, Lew (he preferred the informal version of his name) had grown up in the shadow of his father, who had served as the sixth governor of the state of Indiana between 1831 and 1837, and as an Indiana Congressional Representative between 1941 and 1843 (David Wallace was himself a member of Harmony Lodge 11 in Brookville and joined in 1826). Lew was an incorrigible child who took full advantage of his father the governor’s important positions. He was a notorious discipline problem and in constant search of excitement and adventure, which often landed him in trouble with neighbors. At the age of six he was already threatening to run away from home and stow away on a steamboat.

Born April 10th of 1827, Lew (he preferred the informal version of his name) had grown up in the shadow of his father, who had served as the sixth governor of the state of Indiana between 1831 and 1837, and as an Indiana Congressional Representative between 1941 and 1843 (David Wallace was himself a member of Harmony Lodge 11 in Brookville and joined in 1826). Lew was an incorrigible child who took full advantage of his father the governor’s important positions. He was a notorious discipline problem and in constant search of excitement and adventure, which often landed him in trouble with neighbors. At the age of six he was already threatening to run away from home and stow away on a steamboat.

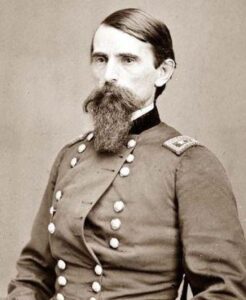

Lew’s father refused to pay for college, so he went to work at age 16 in the Marion County clerk’s office. He began to study law at his father’s law firm in Indianapolis, but in 1846 at the age of 19, he became a recruiter seeking volunteers for the Mexican-American War (1846-48). When the U.S. Civil War began in 1861, he was made the commanding officer of a brigade of Indiana militia volunteers, and was acclaimed for his role in the daring capture of the Confederate Fort Donelson, which overlooked the Cumberland River on the Kentucky/Tennessee border. In 1862 at the age of 34, he was made the youngest major general in the entire Union army.

Lew’s military career and reputation were wrecked by the Battle of Shiloh, after a miscommunication over confused orders issued by General Ulysses S. Grant contributed to an enormous number of Union casualties. Wallace had acted properly and successfully led his troops during the battle, but he became Grant’s scapegoat for many years during and after the end of the war for the terrible losses. Lew was stripped of active command, and what had looked like a brilliant future military career was brought to a sudden and ignominious stop. He was furious at Grant’s betrayal and spent years trying to restore his good name and character. Nevertheless, he continued to serve with distinction wherever he could throughout the conflict, later leading local volunteer troops to repel Confederate attacks on Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. It wasn’t until Grant wrote his autobiography in the 1870s that he admitted his own errors at Shiloh in print and finally vindicated Lew Wallace.

Lew’s military career and reputation were wrecked by the Battle of Shiloh, after a miscommunication over confused orders issued by General Ulysses S. Grant contributed to an enormous number of Union casualties. Wallace had acted properly and successfully led his troops during the battle, but he became Grant’s scapegoat for many years during and after the end of the war for the terrible losses. Lew was stripped of active command, and what had looked like a brilliant future military career was brought to a sudden and ignominious stop. He was furious at Grant’s betrayal and spent years trying to restore his good name and character. Nevertheless, he continued to serve with distinction wherever he could throughout the conflict, later leading local volunteer troops to repel Confederate attacks on Washington, D.C. and Baltimore. It wasn’t until Grant wrote his autobiography in the 1870s that he admitted his own errors at Shiloh in print and finally vindicated Lew Wallace.

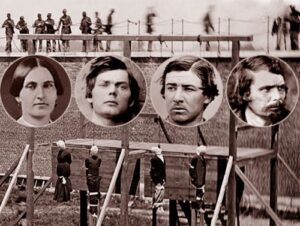

Following the assassination of Abraham Lincoln by John Wilkes Booth in April 1865, Wallace was appointed to the commission that investigated and convicted eight co-conspirators in the murder plot. He was also appointed as the head of a committee that court martialed Henry Wirz, the former commandant of the South’s notorious Andersonville prison camp. Out of 45,000 Union troops held prisoner in the woefully over-crowded camp, more than a third of them had died from dysentery, scurvy and starvation. Wallace was in a unique position to investigate the actions of Wirz because he had briefly served in 1862 as the commander of one of the North’s own prison camps, Camp Chase, in Columbus, Ohio. Wirz was found guilty of war crimes by the commission and executed.

Wallace had long wanted to write novels. In the 1840s, he had written a manuscript called The Fair God, but it wasn’t published until 1873, and it was only marginally successful. But it was enough to convince Lew he had a future as a novelist. After the war ended, Wallace returned to his home in Crawfordsville and began to work on what was first intended to be a short novel about the Magi, the three “wise men” who follow the Star of Bethlehem to Nazareth and pay homage to the newborn baby Jesus. On a train trip in 1876, Wallace had encountered a man named Robert Ingersoll, who was nationally known as “The Great Agnostic.” Ingersoll was an extremely opinionated and powerful orator who advocated what was then known as “Free Thought” in all matters—what would probably be called a “Progressive” these days. Ingersoll advanced the writings of Thomas Paine from the previous century and the belief that the Bible had been written, not by the word of God, but by the well-intentioned hands of men who had simply made up miracles, virgin births, and resurrections.

Continue reading “The Masonic Apron of Major General Lew Wallace, Author of Ben-Hur”