- Morgan’s Raiders and the Jewels of Versailles

- George Washington’s Lodge Bible In Indiana Through February 22nd

- Grand Lodge of Kentucky loans historic Daveiss Sword to the Museum

Morgan’s Raiders and the Jewels of Versailles

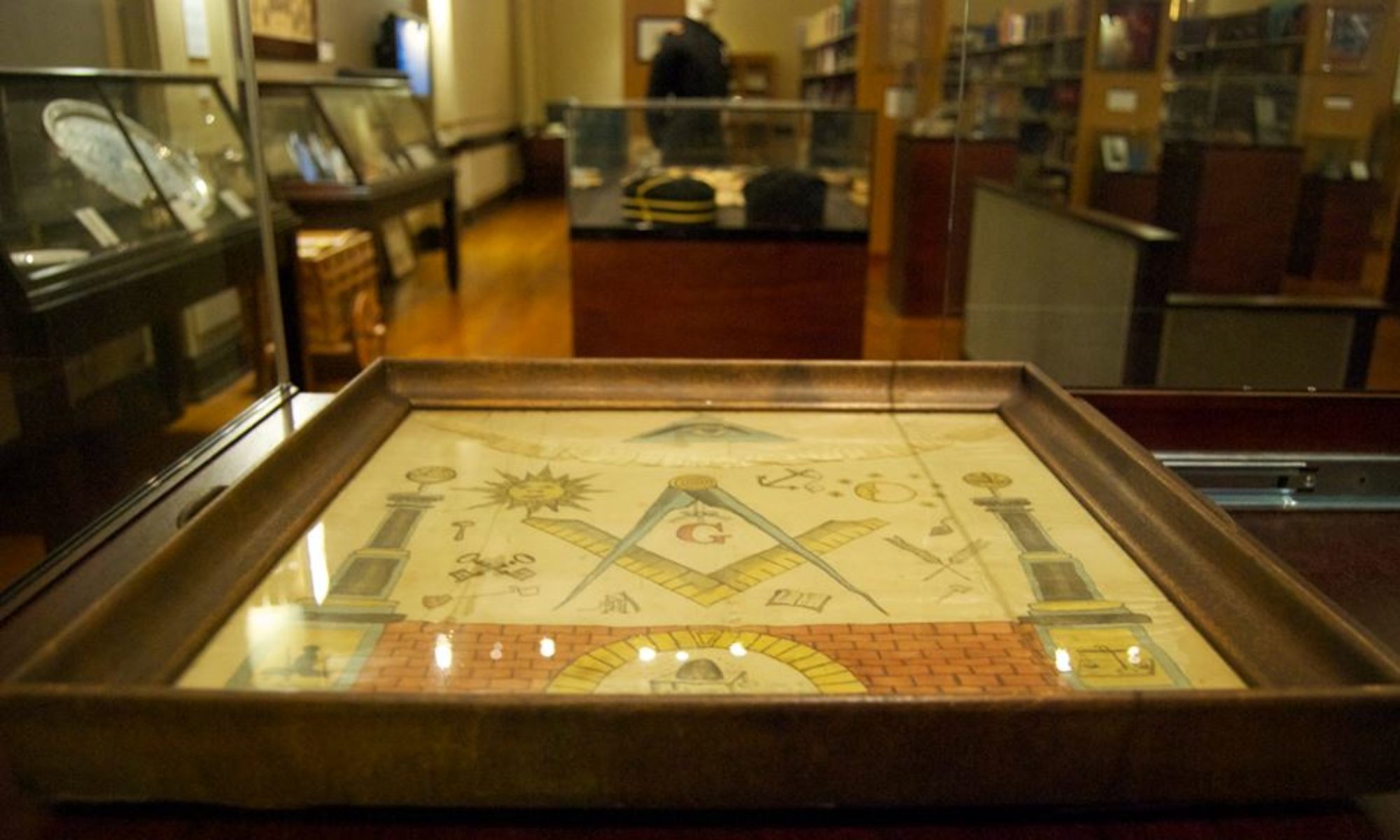

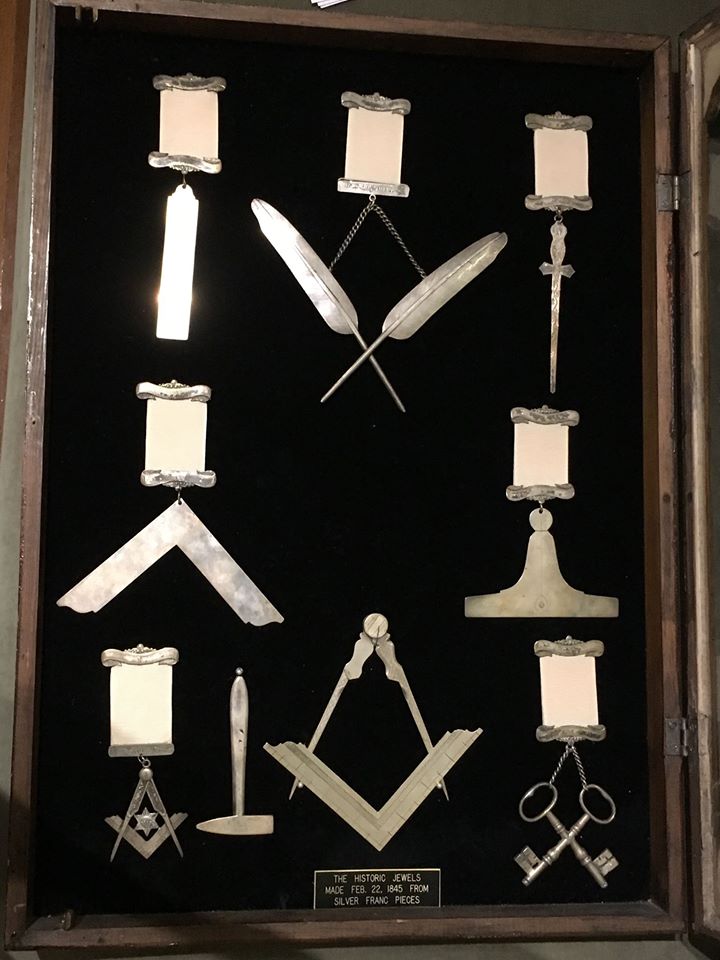

Just in time for the Annual Communication in May, the Masonic Library & Museum of Indiana has been graciously loaned this significant display from the Civil War era by Versailles Lodge No. 7. The jewels will be on display through June of 2018.

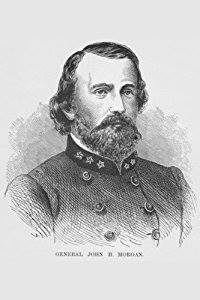

The expedition set out from Sparta on June 11, 1863 with the blessing of Confederate General Braxton Bragg, but Morgan had lied to his superior officer. Bragg had confined his authorization to just Tennessee and Kentucky, but Morgan’s plans from the start were to ‘invade’ the North by crossing the Ohio River.

At that time, Versailles Lodge No. 7 occupied a tiny hall on the second floor of the brick Ripley County office building, on the southwest corner of the town square. A Confederate soldier burst into the Masonic hall that afternoon, spotting something of value – a set of silver officers’ jewels – and made off with them. The jewels had been created when the lodge had been re-chartered in 1845 out of silver French franc pieces, and were treasured by the lodge.

There is one other connection between Morgan’s raid and Versailles Lodge No. 7. When Morgan crossed into Indiana on those two steamboats, he ordered the Alice Dean to be burned. In 1966, workers excavating for a footing for a new bridge at Mauckport discovered the burned timbers of the boat. Brother G. C. Rainbolt of Pisgah Lodge No. 32 in Corydon subsequently presented a hand-made gavel to the members of Versailles Lodge No. 7, made from the rediscovered wood of the Alice Dean .

There is one other connection between Morgan’s raid and Versailles Lodge No. 7. When Morgan crossed into Indiana on those two steamboats, he ordered the Alice Dean to be burned. In 1966, workers excavating for a footing for a new bridge at Mauckport discovered the burned timbers of the boat. Brother G. C. Rainbolt of Pisgah Lodge No. 32 in Corydon subsequently presented a hand-made gavel to the members of Versailles Lodge No. 7, made from the rediscovered wood of the Alice Dean .- Dupuy, Trevor N., Johnson, Curt, and Bongard, David L., Harper Encyclopedia of Military Biography, Castle Books, 1992.

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War: A Narrative. Vol. 3, Red River to Appomattox. New York: Random House, 1974.

- Hodapp, Christopher L., Heritage Endures: Perspectives On 200 Years Of Indiana Freemasonry, Indianapolis, Indiana. Grand Lodge F&AM of Indiana, 2018.

- Smith, Dwight L., Goodly Heritage, Indianapolis, Indiana. Grand Lodge F&AM of Indiana, 1968.

- Archival material of Versailles Lodge No. 7, Versailles, Indiana

By Christopher L. Hodapp

George Washington’s Lodge Bible In Indiana Through February 22nd

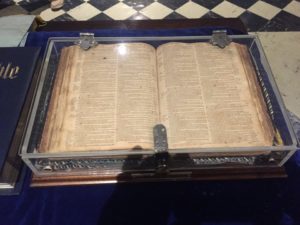

Most Masons are aware that the Holy Bible upon which George Washington took the first oath of office as President of the United States was borrowed at the last minute from New York’s St. John’s Lodge No. 1 in 1789. But very few realize that there is another Masonic Volume of Sacred Law that our most celebrated American Brother was first associated with, almost forty years before he became President.

When he was just twenty years old, George Washington was initiated on the evening of November 4th, 1752 into the newly established “Lodge of Fredericksburgh” in Virginia. That night, he placed his hand upon the lodge’s 1688 edition of the King James Bible and took the obligation of an Entered Apprentice. He would receive his Fellow Craft and Master Mason degrees over the next nine months upon that same Bible, raised at last to the Sublime Degree on August 4th, 1753. This extraordinary 330 year old artifact has been preserved by Fredericksburg Lodge No. 4, and survives to this day.

The Indiana Territory was once a part of Virginia’s westernmost boundaries, and our own early lodges received charters from Kentucky lodges that first began life as part of the Grand Lodge of Virginia. Now, as part of the celebration of the 200th anniversary of the founding of the Grand Lodge of Indiana, our Masonic Library and Museum will display George Washington’s rarely seen Masonic Bible for a very limited time. From now through February 22nd, through the gracious permission and cooperation of our Virginia brethren, it can be viewed by both Masons and the general public. The Masonic Library and Museum of Indiana is located on the 5th floor of Indiana Freemasons Hall at 525 North Illinois Street in downtown Indianapolis.

— Michael D. Brumback, PGM and Christopher L. Hodapp, PM. Originally published in the Indiana Freemason, “Washington’s Bible on display at Our Museum”, Winter 2018, p. 13.

Grand Lodge of Kentucky loans historic Daveiss Sword to the Museum

It may be an abuse of posterity to suppose that any one group of men could be enough of an influence to alter the course of history. The past has a taste of inevitability. But as Americans we were once commonly taught that the mere presence of a singular group of men, Washington and Adams, Jefferson and Franklin, Otis and Hancock, steered a nation toward Man’s first experiment in liberty and self–governance, preserving that experiment from the sort of bloodbath that marked the revolution in France. And yet, were it not for such significant men, this country would have unquestionably had a very different destiny. For a Hoosier, a walk along the Wabash Trail, from an isolated frontier fort to an historic battlefield where Kentuckians and Hoosiers fell side by side, encompasses the whole of our settler past, a tiny strip of territory where a group of similarly remarkable men secured a new state.

It may be an abuse of posterity to suppose that any one group of men could be enough of an influence to alter the course of history. The past has a taste of inevitability. But as Americans we were once commonly taught that the mere presence of a singular group of men, Washington and Adams, Jefferson and Franklin, Otis and Hancock, steered a nation toward Man’s first experiment in liberty and self–governance, preserving that experiment from the sort of bloodbath that marked the revolution in France. And yet, were it not for such significant men, this country would have unquestionably had a very different destiny. For a Hoosier, a walk along the Wabash Trail, from an isolated frontier fort to an historic battlefield where Kentuckians and Hoosiers fell side by side, encompasses the whole of our settler past, a tiny strip of territory where a group of similarly remarkable men secured a new state.

For any historian with a romantic bone in his body, its hard not to personalize the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 11, 1811 in terms of the ongoing grudge match between the legendary figure of Native American warrior chief Tecumseh versus the Indiana Territorial governor, General William Henry Harrison. Tecumseh was away at the time, attempting to organize more warriors to join his cause of uniting the Indian tribes to turn back white settlement. Tippecanoe was a win for Harrison, and the chief blamed his brother, Tenskwatawa, who was called “The Prophet,” for the loss, banishing him for life. Weeks after the battle, Tecumseh returned to ride through the ashes of Prophet’s Town and swore to meet Harrison again in battle. They did indeed meet again, at the Battle of the Thames in Upper Canada in 1813, where the great chief finally fell. Harrison went on to become President.

But for Masonic historians, Tippecanoe is seen through another lens, that being the number of Freemasons present and among the fallen. Considering that Vincennes Lodge had only been raising Indiana Masons for two years, it’s an impressive number of brave men, but there’s a reason for it. Many of the officers and men who died were Kentuckians, members of the parent lodges that gave birth to the lodge at Vincennes. In their joint fight for the Territory of Indiana, the ties of Masonic brotherhood between them are carved for all time on the lists of the dead at the memorial raised on the Tippecanoe Battlefield. It’s now a part of the Wabash Heritage Trail, thirteen historic miles through and around Lafayette, running appropriately from Fort Ouiatenon to the battlefield of Tippecanoe. It’s something every Hoosier should see, not only for its incredible natural beauty, but for the historic markers that give three-dimensions to our history.

For Freemasons, key events were unfolding in Vincennes Lodge a week before members left for the battle. Easily the most significant Masonic episode to occur in the Indiana Territory during the pre-Grand Lodge period was the visit of the Virginia-born Grand Master of Masons in Kentucky, Colonel Joseph Hamilton “Jo” Daveiss, to the lodge at Vincennes, then Kentucky’s Vincennes Lodge 15. Daveiss was on his way with troops to the upper Wabash country to face The Prophet and his warriors. On three evenings—September 18, 19 and 21 of 1811—the Grand Master met with his brethren at Vincennes, conferred all three degrees, and raised one Brother in particular.

Many new friendships were forged in that week, and old ones were strengthened by the knowledge of the coming conflict with the Indians. One of these friendships was between Jo Daveiss and Colonel Isaac White, another Virginian, now a Hoosier. The men were of an age, and thought much alike. White was college-educated, and he’d been in charge of the salt works at Saline River, sent by the Governor, salt being a necessary commodity for food preservation, and at that time in short supply. He had been a captain in the Knox County militia, later raised to a colonel, and was a popular man in Vincennes, handsome and with a winning manner. He had originally volunteered to go with Governor Harrison, but the Governor said he had plenty of men when he left to head north, and hoped a battle wouldn’t be necessary on that account. And so, at Vincennes Lodge, White volunteered into the Kentucky Dragoons led by Daveiss, instead. He was one of a dozen officers who fought officially in the battle as privates for this reason, which has often led to a baffling confusion of proper military titles by writers in later years.

On that night in September, Daveiss and White knew they were going into battle together. The two men had formed a deep friendship, and so they exchanged swords. According to an 1889 memorial written by Jo Daveiss’ grandson, it was White’s sword he would carry into battle. In his book Goodly Heritage, Dwight Smith relates the story of Judge Levi Todd of Indianapolis, a Past Master of Montgomery Lodge No. 23 at Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, who came to have Daveiss’ sword and belt in his possession. This was around 1860, and he’d once been a law student of Daveiss’ in his Lexington law office. The sword was given to him by Daveiss’ widow, and he presented it to Grand Lodge of Kentucky. It is this treasured artifact that the Grand Lodge of Indiana has been graciously loaned by Kentucky to display at the Masonic Library and Museum in Indianapolis for our Bicentennial year.

An amazing number of men fighting in General Harrison’s army at Tippecanoe were, or later became, prominent Freemasons, especially considering that the first organized lodge in Indiana had only been chartered two years before. Members of Vincennes Lodge 15 in the fight included William Prince, member of the Territorial Assembly, and Parmenas Backes, later sheriff of Knox County. Others in the battle who went on to found the Grand Lodge of Indiana included: Major Waller Taylor, Territorial judge and Indiana’s first U.S. Senator; General Washington Johnston and Benjamin Beckes of Vincennes; Joseph Bartholomew, later of Charlestown; John Tipton and Davis Floyd, later of Corydon; and Marston G. Clark, who settled at Salem.

Jo Daveiss went on to lead a courageous strike against the Indians at Tippecanoe where he fell, wounded in the chest, and Isaac White died not far from him. The bodies of the Kentucky Grand Master and the newest Master Mason in the Indiana Territory were laid in the earth side by side, their battle cloaks wrapped around them. Thomas Randolph, who had constituted Vincennes Lodge 15, and Colonel Abraham Owen of Kentucky’s Solomon Lodge 5 from whom the lodge received their first charter were among those to fall on the field of battle at Tippecanoe. Other men died that day, Kentuckians and Hoosiers, but the story of Daveiss and White struck a deep chord at the time, a note of unity of the two states, and of courage. And of Masons. Few know it today, but Indiana might just as easily become a Spanish territory under the traitorous plotting of Vice President Aaron Burr, whom Daveiss had battled in a Kentucky courtroom five years before. Men like him and others who were among Kentucky and Indiana’s first Masons kept Indiana safe, and free, and a part of America.

A Masonic marker erected by the Grand Lodge of Indiana in 1966 stands today near the Tippecanoe Battleground Monument. Indiana’s Freemasons first proposed a tall, columnar monument in the 1830s with contributions from Kentucky brethren, as well. However, when so little money was raised for the project, it finally vanished from further consideration after the 1850s. The present obelisk was erected in 1908. In 1929, a much smaller stone marker was also erected by the Daughters of the American Revolution at the base of the large stone outcropping along Burnett’s Creek known as “Prophet’s Rock,” where The Prophet chanted and sang to encourage his warriors during the fight, assuring them the white man’s bullets would not pass through their bodies.

The Daveiss Sword is just one of several very special exhibits that will be displayed throughout the Bicentennial year of 2018 that tells the story of Freemasonry at the Masonic Library and Museum of Indiana. But always remember that Masonic history is never isolated to just a handful of members or “important” lodges. Every single lodge, large and small, new or old, has a past with stories to tell. Take this opportunity of the Grand Lodge’s 200th anniversary to pour through your own lodge’s archives to discover the hidden nuggets of lore that will help bring the past alive for all of us.

— Christopher L. Hodapp, PM. Originally published in the Indiana Freemason, “The Joseph Daveiss Sword”, Winter 2018, pp. 6-8.